Deworski Odom does not do a lot of talking. You get the feeling after spending a little time with him that he is one of those coaches who can communicate with his athletes from across a track. A raised hand. A stare. You get the distinct idea that athletes know exactly what he wants, and that they will do exactly that. Or there will be consequences.

That's the thing about Deworski. He is accountable. He takes personal responsibility for helping his athletes to become better in not only their events, but becoming better people who can succeed in life.

That's the thing about Deworski. He is accountable. He takes personal responsibility for helping his athletes to become better in not only their events, but becoming better people who can succeed in life.

And he takes his craft very personally. So much so that he tends to simply concentrate on observing his athletes to understand exactly what he has to do to help them become technically sound.

Deworski Odom is a product of a lot of incredibly hard work… some of the best coaches in the world… a mother who always kept him grounded… and yes, a little bit of luck.

Basketball was, is,

and always will be Odom's favorite sport.

To this day, you can follow his passion for the sport on his twitter feed. During games, between seasons… pretty much all year round.

After Odom's dad died, his mother, Lessie, moved he and his two sisters to Philadelphia from Georgia when Deworski was ten. The year was 1987. Philly Public League basketball was at its height. Overbrook happened to be the high school of all-time great Wilt Chamberlin. And Odom was ready to take all that basketball could give him. "All I remember is being in the street and racing from pole to pole."

Odom had no idea that track was an option.

When he entered junior high school at Shoemaker Middle School, Odom was on the small side. "I couldn't even make the relays. I couldn't do anything."

Odom was a bit miscast and was put in the 2 mile, the mile and the 800. "I was horrible at it," he says with a slight grimace.

His journey to the hurdles was not the most direct. He actually spotted another athlete -- Naomi -- who was a hurdler. "I had a crush, so I asked her to teach me the hurdles."

"I ran right through them."

His middle school coach, Kenneth Sturm, made a speech to his athletes before sending them on to high school. "Some of you will go and be athletes, and some of you will be students."

Too small for football, and not the best (tallest) basketball player, Odom was convinced he'd be a student.

Legendary Overbrook coach Fred Rosenfeld got him to run cross country. But it wasn't long before Odom decided it wasn't for him.

Track was not even on his radar.

Some of his classmates had decided they wanted Odom to run indoor track. So he joined the team. But what hactually excelled at was skipping practice.

"The seniors on that team saw some talent in me, and said if you don't come to practice, we're going to beat you up." (Editor's note: this is probably not recommended as a recruitment tool in 2013).

Odom remembers talking a little trash with the guys and then taking off yelling, "Ya'll not catching me."

The seniors decided that Odom was worth the effort. "They thought I was ridiculous fast."

So the next time Odom talked trash and took off running, the guys had others coming from the other direction and from behind. He was trapped. And they delivered on their promise with the warning… "You better be at practice every day or we'll do this every day."

"That one time was enough," Odom recalls. "These were some big dudes."

And to this day, every time Odom sees one of those former teammates, he thanks them.

"There never would have been a Deworski Odom without them."

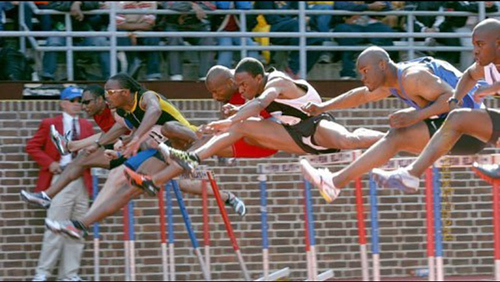

Odom was considered primarily a hurdler, but his sprints have also stood the all-time test in the US.

PA All-Time Bests

Indoor

55 H 7.08

Deworski Odom, Overbrook 1995 #4 AT US

60 H 7.62

Deworski Odom, Overbrook 1995 #3 AT US

55m 6.16

Deworski Odom, Overbrook 1995 #8 AT US

60m 6.62

Deworski Odom, Overbrook 1995 #2 AT US

BELOW: Odom with the great William Reed, Central HS

Outdoor

Outdoor

100m

10.0h

William Reed, Central 1986

and

10.26

Deworski Odom, Overbrook 1994 #24 AT US

110 H

13.54 -1.2w

Wellington Zaza

Garnet Valley

June 16, 2013 @ New Balance Nationals Outdoor, Greensboro, NC

Was 13.3h by both Rodney Wilson, Bartram 1979 & Charles James, Harry S. Truman 1983

+ 13.61 Deworski Odom, Overbrook, 1995

As a junior at Overbrook, Odem clocked what was pretty quick for a high school junior, going 10.26 at the IAAF World Junior Championships. That remains, along with William Reed's (Central) 1986 hand time of 10.0, the fastest ever run in the state. He actually came into the world meet with a PR of 10.38; had won the Juniors trials in Florida in 10.51.

(Note: Reed also holds the PA all-time mark in the 400 of 45.17)

You would think that Odom would have been pleased with a 10.26 and his bronze medal on the world stage -- especially running against seniors and college freshmen (Juniors is 19 and under).

He was not.

NSSF (Now NSAF) co-founder Mike Byrnes -- who was with the US team for the meet -- congratulated Odom on breaking the American Junior record.

Odom's response to Byrnes?

"I lost."

"Yeah, but…" Byrnes insisted.

"Yeah, I lost."

His recollection of the race was he came into the finals with the fastest time (10.42 in the prelims)… so he had a middle lane.

The gun goes off and Odom is in the lead. His first thought?

"I'm running too fast. These are men I'm racing."

The "men" included future Olympic medalist Obadele Thompson of Barbados and future Olympian Dwanye Chambers of Great Britain.

Odom pulled his head back and after crossing the line, heard 10.24-10.25-10.26.

"I was mad."

It would take seven months for Odom to realize what he had accomplished, and it finally hit home when Sports Illustrated came to Overbrook to do a Faces in the Crowd and a story.

Odom says that that race was the fire he needed for all future races. "I felt sorry for the public league and PA for my senior year.

Indoor was his opportunity to take out his frustrations on other high schoolers.

Odom still holds the PA all-time records in both the 55 and 60 dashes and both indoor hurdles in PA… but believes that those might be even faster if he had been able to run at Penn State instead of Lehigh.

"I would have killed on that track."

His 6.62 60 meter dash was the national record for 14 years until it was broken in 1999 by Casey Combest of Kentucky at NBIN in Columbus, Ohio.

He had never run the 60 before he faced favorite Brian Howard from California at the indoor nationals. Howard still holds the 50 meter dash US record. But Odom didn't care about time. He won. Having never run the distance, Odom thought was an advantage for him. "I even geared down for the last five meters."

Outdoor, Odom never got the chance to run in the PIAA state meet because the Philly Public League was years away from joining the state association. Odom considers Penn Wood legend Leroy Burrell's 10.44 at the PIAA state champs and the record. "I was not the rightful owner," he says quite succinctly.

But that didn't stop him from owning the outdoor 110 meter hurdles PA all-time best. His 13.61 stood the test of time, until it was broken at the NBON in June by Garnet Valley grad Wellington Zaza.

"I only ran the 110 three times my senior year. I had run 13.64 at Golden West, but that was fifteen minutes after running the 100.

"Not taking ANYTHING away from Zaza's record, I believe my hurdle times would have been 13.30, hands down."

To be clear, Odom wanted Zaza to get the record. "I actually wanted him to get it at the state meet… but the finals is always about the win."

It wasn't until the finals at NBON in June that Zaza went 13.54 to claim the record. Unfortunately, Odom, who was coaching at the meet, was not able to see the race. "I did tweet 'I'm proud of you' to him, though."

A Long Journey through College.

Even though then departed (for Central) Overbrook coach Fred Rosenfeld had preached academics to his charges for years, Odom had not entirely paid attention. He took the SATs only once and started his collegiate career at Wallace State Junior College.

"I never thought about college, but the 10.26 had everyone talking. My mom had no money, and I had two sisters, so I started to get the books together. People never gave up on me."

At Wallace State, Odom won the junior college nationals in the 55 hurdles. But an injury he had sustained to his hamstring at Nike Nationals in his senior year would come back to haunt him.

At Wallace State, Odom won the junior college nationals in the 55 hurdles. But an injury he had sustained to his hamstring at Nike Nationals in his senior year would come back to haunt him.

"I knew it was going to happen… always running people down 40 meters out. I wasn't in the weight room. I knew I was built to run really fast but I could never really pull that other gear, because I knew I'd strain my hamstring."

Odom had been told he was so explosive that his body could not maintain the effort.

By his sophomore year at Wallace State, the hamstring was still injured. "I was putting a lot of pressure on myself. I was rough on my roommates, but they didn't take it personally. They knew what I was going through."

One of his competitors told Odom that injuries happen to the best.

"That comment made me take a couple of steps back. I had been told I was not human… it never set in. That was a reality check."

His original plan had been to transfer from junior college to a Division I program. Clemson was one choice. A big-time Alabama fan, he would wind up joining the Crimson Tide. But when the coaching staff was dismissed, Odom was released from his scholarship.

He would come home, planning to join another Division I program.

Hurdler Rodriguez Fister, who went to Texas A&M told him about a great program and coach in Raleigh, North Carolina -- Saint Augustine's, coached by the legendary George Williams.

Realizing it was Division II, Odom said no. "I'm better than that."

But Williams reached out to Odom, and told him… "if you give me everything, I'll give you everything back. People will criticize you and say you're too big. But you'll succeed."

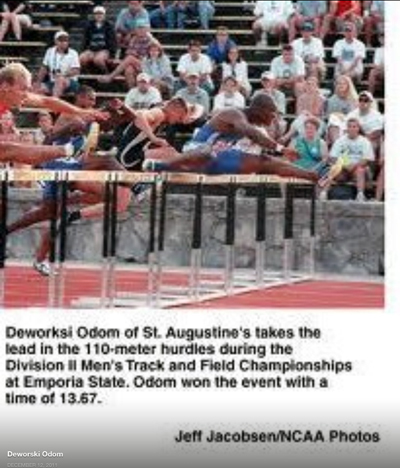

Odom did not win a single meet his junior year at Saint Aug's until the DII Nationals Championships when he captured 2nd in the 55 and won the hurdles.

Odom did not win a single meet his junior year at Saint Aug's until the DII Nationals Championships when he captured 2nd in the 55 and won the hurdles.

Odom would never lose after that. "I was on a mission. I remembered the struggles."

"Coach Williams is like a dad to me."

Look who I met!

During his senior year at Saint Aug's, Odom went to a golf tournament and ran into John Capriatti.

"I had on a Nike hat and shirt. I certainly did not know who he was. He said 'how'd you like to run for them (Nike)'. I said, 'I wish'. And he said, 'I can make that happen'."

Odom's coach asked him if he knew who Caprietti was… and was told he is the guy who does contracts for Nike.

An hour later, contract.

"Hell yeah!" says Odom. Bonus.

"I was still in school, but went pro early."

Odom finished as a 16 time all-American with two D1I titles, and record holder in the hurdles.

Odom has a lot of fond memories from his pro career, but his first description of the process is "The snakes come out. A percentage here and a percentage there. Maybe I could have made some better business decisions. Maybe some better coaching."

But his list of his favorite coaches includes some who might make you take a second glance.

Trevor Graham tops his list.

At the head of the BALCO doping scandal, Graham has a lifetime ban from the US Olympic Training Center.

Odom credits Graham with helping him develop a fix to an imbalance in his stride. The solution was a seemingly simple one the two worked on together -- keep one hand open while he runs, and the other one cupped.

But even with the drug scandals, Odom still has the deepest respect for what Graham did for him. "I love that dude."

Odom was training partners with Marion Jones and Tim Montgomery, both of whom were caught up in the BALCO scandal.

Odom says he still talks with Tim and Trevor. Jones, not at all.

Obviously, 2004 Men's Olympic Coach and long-time Saint Aug's coach George Williams makes Odom's all-favorites list… along with Saint Aug's hurdles coach Tim Chapman… and Stan Marusky… "…who believed in me when I was going to quit."

From high school, Odom fondly remembers Fred Rosenfeld. "I never reached my potential with him. He was more in my ear academically. And I was really mad when he went to Central. Coach Rose was the face of Overbrook. No disrespect to others, but he was."

Odom says there are many out there who say they coached him. "I don't worry about it too much… but I know I got more than a few people a job."

How Odom found his way back to 'Brook.

One career ends and another begins.

One career ends and another begins.

Odom does not mince words.

"I didn't want to coach. I wanted to make a comeback."

When Nike cut Odom, he was depressed. "My whole lifestyle changed. The way I was living. I was not talking. I just started crying."

Coach Sturm approached Odom and said he was needed at Overbook.

"I talked with my mom and she told me I had to find yourself. She said 'you have to take this coaching stuff seriously, like you took running seriously. Give those kids everything."

Odom says he woke up the next day and said 'that is what I'm gonna do.'

"That first day at 'Brook, I was stuck. It had gone down so far, I had to build it back up. That was my own personal challenge."

Overbrook had remained competitive when Rosenfeld left, but started going downhill a couple of years after Odom left. There were many coaching changes.

What Odom found was bad.

"Kids would wear regular street clothes to go to the meet to warm up. I simply said 'this will not happen on my watch.'"

The big change came in attitude.

Odom's rules:

1. No profanity.

2. It's all about respect. CHARACTER can take you a long way in life.

3. There is no such thing as luck in track. "I don't wish my kids luck before a race. They know where they're at."

4. Be a professional in everything you do. If it's something you really want to do, take it personally. Give it your all. Full throttle.

On occasion Odom has been forced to suspend an athlete from the team. He does it with the simple charge… 'We don't do that at 'Brook. You're not just representing yourself, your school, your family and me… and it clicks."

"Usually they end up giving me everything."

But the bottom line for Odom is, "those kids are the best thing that ever happened to me. I'm happy around them. I joke with them. But they know when the other Coach D is around, and do what's right."

Odom mostly avoids other coaches simply because he is so focused on the kids.

"Dealing with other coaches. I think I could write a book."

He isn't avoiding anyone though. He simply has no time… and it would take away from the kids.

But he can't help but to offer a general observation.

"I always thought it was about the kids. And it's not. It's more so about them. But there are some really good coaches."

For one, Odom is a true fan of Lenny Jordan at Penn Wood.

"He is a guy I call for advice. It is not about him, it's about his kids. He is not worried about being liked by other coaches, but his kids love him."

We use each other for support and as a sounding board.

Another coach on Odom's "cares about his kids" is legend Tim Hickey (formerly of William Penn, West Catholic and now at Swenson.)

"Hickey took me to Golden South to get me exposure when I was in high school. He didn't have to do that."

Odom says one of his favorite "I can't believe they're saying that about me" times is when people don't know who he is sit beside him and say things like 'I hear he is arrogant… that's what everybody is saying?'

"I sit back, wait until they're finished, and say 'Well, I'm Deworski Odom. How ya doin'. Oh, and don't believe all you hear."

Odom admits to having showboated a couple times during his career. But only in high school and college… never as a pro. "When it happened 'I felt horrible. It wasn't me. I am very aggressive in running. But you should never show somebody up."

"I tell my kids, they'll find out who you are when you are faster than them."

Odom is a bit scared for Philly's public schools.

But he stays because he sees hope.

Odom has some strong (valid) opinions about some of the causes in the decline of public schools.

"If parents cared a little more, it would not have happened."

"And Charter schools blew up public schools. When (national class) basketball left the public schools, then it was done.

"I pray for this generation. I could not come up in this generation -- with the school situation and community. In my time, athletes were protected."

What does he say when kids ask him where they should go? "I tell them that your team is what you need. You all have the same goals to get better and to make a life. It helps them to get away from what's going on in their community or their own home… to be around people who care. That is their whole outlet and the only time they can smile."

And Odom is a staunch defender of track as the sport that deserves to be kept when others may be cut.

He maintains that track athletes have the highest rate of attending college… and that the sport is cheaper to support than others.

As for his coaching salary?

"What the district pays me goes right back. They pay fees, and I pay the transportation."

"My mom thinks I'm crazy." 'If you were married, you'd have problems', she tells him. "But I come at them like they're my kids."

On Zaza and a little bit of trash talk.

"I had heard so many things about Zaza. But I never saw anything negative. I just saw a talented, focused athlete."

Before the state championships, Zaza was on the track and asked Odom if he thought he could still hurdle.

"I said 'what do you think?'"

Zaza has his doubts and sets up a hurdle.

Odom rolls his pants leg up. He was already warmed up after doing a workout.

Boom. Over in the blink of an eye.

"Once you got it, you got it."

Zaza's response? "Your lead leg is faster than my lead leg."

Odom's reply? "I do this son. I made a lot of money doing this."

Odom admits to not being at an ideal weight. And he is doing something about it… "I want to get fit. Health is important. I knew I would gain weight, but at the time, I didn't care. Now I do."

Be warned sprinters and hurdlers, some Masters competition is in Odom's future.

One athlete who brought out the best of Odom.

Last year… Odom had what he described as a 'love-hate' relationship with Cierra Brown. And he means that in the nicest way. And it was mutual.

"Grueling," would be the best description, Odom shares. "But I never gave up on her."

He was direct with her. She needed to change some things about her approach to life.

She had run a 67 400 as a frosh. She was getting the work in but she didn't think she was. She finished the season at 64.

She worked over the following summer and came back and ran 57 and made states, also going from a 2:17 to 2:11… 2:12 indoor. Her 2:11 would take the Silver at States against three-time champ Emma Keenan of Gwynedd Mercy.

"It was grueling, but such a challenge. I loved it. She brought the best out of me and visa versa. She started believing in her talents and listening."

"Other people went to her and said do you realize who your coach is?

And it clicked. She had a male mentality. Aggressive. The boys hated running with her. She'd elbow them and say get out of my way."

'Brook was Odom's destiny.

He was told in college he would eventually coach kids.

Odom went on to graduate from Saint Aug's with a degree in education with a minor in criminal justice and one in child development. He first tried criminal justice, but simply didn't like it.

Currently he works at the Mariana Bracetti Academy Charter School in Kensington in the Special Education and Behavior department.

Coaching and working in a program like he does was something he was told was in his future. As a senior at Saint Aug's, the college had a community day when kids were invited to the track where they went through some drills. These were little kids and Odom said he was 'acting like a fool with them'.

One of the people there told him he was really good with kids. And he looked at her and said 'ME?' She replied: 'I promise you, you're going to work with kids.' The year was 1998.

He told her he would be running for Nike and going pro. She said 'you may do all that, but before it's over, you will be working with kids.'

What's next for Odom and 'Brook?

With no hesitation, Odom says that the Overbook guys will have a 4x800 that will run 7:50 next year. As proof, he offers: "We had a kid run 36 in xc who did 2:05 his first time on the track in the 800. We have two juniors at 1:58. Right now, our slowest leg is 2:09. We'll do 7:50."

"It is a tempo race. So we do 600's all day with short recovery. You train fast, you race fast."

To get some pointers, Odom talked with four-time 800m Olympian and US Record-Holder Johnny Gray… who told him that if it's working, don't question yourself. Keep doing what you do.

That's good enough for Deworski.

Odom respects athletes, like him,

who have been driven to prove people wrong.

At 6-2 and 180 pounds as a pro, Odom was said to be too big to sprint and hurdle at a world class level.

But, he says, what he had was pure speed that was helped tremendously by being technically sound… from his foot strike, to his altered hand positions, to achieving proper angles.

"That's what coaches loved about me."

And he had fight. Fight to do his training as it was given to him. Fight to compete to win in every race. And fight to prove to people that he was as good as his performances would suggest.

And the basketball fan in him (still his favorite sport), has respect for athletes like Lebron James.

"He reminds me of my fights. He just had to prove everybody wrong."

So the next time you see Deworski Odom standing on an infield observing his runners… or standing on the side simply staring at an athlete who is not doing what is expected, don't interrupt him. He is hard at work and he doesn't have time to talk.

First of all, to Odom, the kids come first.

And lastly, Odom lets performance do his talking.